Accessible by Design: Building Inclusive Digital Products from the Ground Up

- Nir Horesh

- Jul 11

- 9 min read

"We're building this product to be accessible by design," they say confidently in the project kickoff meeting. Fast forward to the end of the development cycle, and there's a frantic scramble to run automated accessibility tests, add alt text to images, and fix color contrast issues before the QA team flags them as blockers.

"Accessible by design"—you keep using that phrase. I do not think it means what you think it means.

True accessible design isn't about catching accessibility issues before launch. It's about making accessibility impossible to miss because it's woven into every decision from the very first user story. It's about creating products where accessibility happens naturally, not as an afterthought that requires fixing.

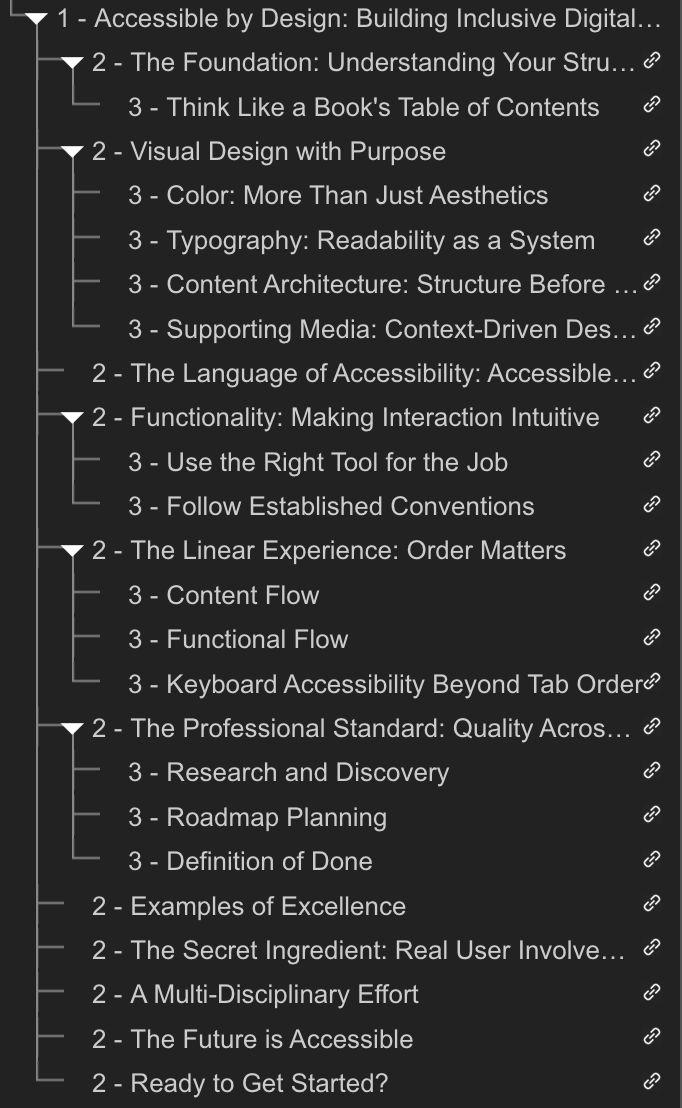

The Foundation: Understanding Your Structure

Before writing a single line of code or creating your first design mockup, you need to understand the fundamental architecture of your digital product. This isn't about visual layouts—it's about information architecture that makes sense to all users, regardless of how they interact with your product.

Here's where accessibility reveals its hidden superpower: it forces you to understand the purpose of everything in your product. You can't write meaningful alt text without knowing exactly why an image exists. You can't create proper heading hierarchy without understanding your content structure. You can't choose the right interactive elements without knowing what actions users need to perform. This isn't just good for accessibility—it's fundamental to professional product design.

Think Like a Book's Table of Contents

Every accessible digital product starts with understanding its structure. Ask yourself:

Which pages will your website or app contain?

What are the main sections (landmarks) on each page?

What is the specific purpose of each page and section?

How do these elements relate to each other hierarchically?

This structural thinking directly translates into your heading hierarchy. Your <h1> tag should tell users what the entire page is about—there should be exactly one per page. Your <h2> tags mark the beginning of major sections, explaining what each section covers. <h3> tags introduce subsections, and so on.

Think of your heading structure as the index of a book. A screen reader user should be able to navigate through your headings and immediately understand your content's organization, jumping directly to the information they need. This isn't just good for accessibility—it's exactly how search engines understand and rank your content.

Visual Design with Purpose

Color: More Than Just Aesthetics

Color choices reveal whether a team truly understands accessible design. When Lyft was developing their design system, they didn't just pick colors that looked good—they built constraints into their color palette that ensured sufficient contrast combinations were the default choice, not an afterthought.

The key insight: instead of hoping designers will remember to check contrast ratios, create a color system where high contrast is built in. This approach scales across your entire organization and prevents accessibility issues before they happen.

Typography: Readability as a System

Just as with colors, approach typography systematically. Plan a font system with as few fonts as possible—complexity breeds inconsistency. Choose fonts that prioritize readability over aesthetics, embracing the principle that form follows function.

Consider font sizes that remain readable across all screen sizes and zoom levels up to 200%. Avoid thin or ultra-light font weights that become illegible when users zoom in or when displayed on certain screens. Remember that what looks elegant at 100% zoom on a high-resolution monitor might be completely unreadable for someone using browser zoom or a lower-resolution device.

Research consistently shows that when readability is optimized, cognitive load decreases, users stay longer on websites, and engage more deeply with content. This isn't just about accessibility—it's about business performance. Every improvement in readability translates to better user engagement and outcomes.

Content Architecture: Structure Before Styling

Only after you've defined your structure and heading hierarchy should you begin adding content. This sequence matters because it ensures your content supports your accessibility goals rather than fighting against them.

Most teams work top-down, starting with text and images, then struggling later to figure out what headings should be and where, or what alt text should say and why. This backwards approach creates confusion and inconsistency.

The recommended work order is:

Define your headings - Establish the page structure and hierarchy first

Add textual content - Fill in the content that supports each heading

Support with media - Add images, videos, and other media that enhance the text

When you follow this sequence, each piece of content has a clear purpose and context, making accessibility decisions obvious rather than guesswork.

Supporting Media: Context-Driven Descriptions

When adding supporting media—images, videos, audio—you should already know exactly why each element exists. If you're thinking "I need an image here to show X and support the previous paragraph," you've just written your alt text. The alt text should describe what's important about the visual content in the context of your written content.

This same principle applies to all media:

Videos need captions that convey not just dialogue but important sound effects and music

Audio content like podcasts need transcripts

Complex images like charts need detailed descriptions that convey the data insights

Today's tools make creating these alternatives easier than ever, but the key is building their creation into your content workflow from the start.

The Language of Accessibility: Accessible Names

Everything visual and interactive on your interface needs an accessible name—a clear, descriptive label that assistive technologies can communicate to users. This goes far beyond alt text for images.

Consider interactive elements like icon buttons. A button displaying a magnifying glass icon shouldn't have an accessible name of "magnifying glass"—it should say "search" because that describes what happens when someone activates it. Similarly, a button with an envelope icon should be labeled "mail" or "contact us," not "envelope."

The accessible name should always describe the action or purpose, not the visual appearance. This principle helps all users understand what will happen when they interact with your interface.

Functionality: Making Interaction Intuitive

Use the Right Tool for the Job

HTML provides semantic elements for a reason. Understanding when to use each element is crucial:

Links vs. Buttons: Links take users to different locations or contexts; buttons perform actions within the current context

Selection patterns: Use checkboxes for multiple selections, radio buttons for single selections from a group

Lists: Use <ol> for ordered lists (with numbers), <ul> for unordered lists (with bullets)

Follow Established Conventions

Users have learned patterns through years of digital interaction. Radio buttons are round, checkboxes are square. Links are typically underlined or colored differently from body text. Violating these conventions creates confusion and increases cognitive load for everyone.

When you make links look like buttons or checkboxes look like radio buttons, you're not being creative—you're creating barriers. Users expect checkboxes to look like checkboxes: squares with a checkmark to communicate selection. Using circles as checkboxes creates confusion because they're easily confused with radio buttons. Following design standards enhances users' ability to predict what a control will do—when they see checkboxes, they know they can select multiple options; when they see radio buttons, they know they can only select one.

The Linear Experience: Order Matters

Your content and functionality must work in a logical sequence. This linear order—the sequence in which elements appear in your HTML—determines how screen readers present your content and how keyboard users navigate your interface.

As long as all content is in a single column, this is straightforward. But when you have multi-column layouts (example 1 below), decisions become critical: should content be read in rows or columns? The semantic order in your HTML must match your visual design intent (example 2 below).

Consider common layout questions: If you have a navigation area on the left side of the page, should it come before or after the main content in the HTML? What about a related content column on the right—where does that fit in the reading order? These decisions need to be defined during design and implemented correctly from the start. It's very easy to get right when creating the product, but very hard to fix after release without major restructuring.

Test Content Flow

Test your content order by using a screen reader with basic navigation commands. Does the reading order make sense? Does the narrative flow logically from one section to the next? This same linear logic benefits everyone, including search engines that index your content.

Functional Flow

For interactive elements, test your keyboard navigation by disconnecting your mouse and using only the Tab key to navigate. The focus order should be logical and predictable. When users activate links or buttons that change context (like opening modals or new windows), where does the focus go? It should move to a logical location that helps users understand the new context.

Keyboard Accessibility Beyond Tab Order

Every interactive element must be fully operable with a keyboard. If you use standard HTML elements, you get this behavior automatically. If you build custom components, you need to implement keyboard behavior that follows established patterns.

The goal isn't just to make keyboard navigation possible—it should be efficient. When done right, many users prefer keyboard navigation because it can be faster than using a mouse, especially for complex forms and workflows.

The Professional Standard: Quality Across All Contexts

Here's the most important insight from my experience: all these accessibility decisions should be made before you write a single line of code. It's dramatically more efficient to solve these problems in your design tools than to retrofit them in production.

This is what separates amateur approaches from professional ones. Accessibility isn't an extra constraint—it's a lens that reveals whether you truly understand your product. When you're forced to define the purpose of every element, the relationship between every component, and the intention behind every interaction, you create products that are not just accessible, but fundamentally better designed.

With the exception of ARIA attributes that are specifically for assistive technology, almost all other accessibility requirements are simply about creating very good websites. Semantic HTML, logical content order, clear navigation, readable typography, sufficient color contrast, keyboard operability—these aren't accessibility features, they're quality standards.

But "accessible by design" starts even before your design phase. It begins with:

Research and Discovery

Include accessibility as part of your product research. If you're creating new interaction patterns, research how they should work for users with disabilities. This research time should be built into your project timeline.

Roadmap Planning

Allocate appropriate time for accessibility work in your product roadmap. Creating accessible components often requires additional research and testing, especially for complex interactions. You'll also need time for accessibility definitions in the design phase and accessibility testing and fixes in the QA phase. However, the more you improve your processes, design systems, and component libraries to have accessibility built in, the less overhead it becomes in future work—the investment pays dividends over time.

Definition of Done

Include accessibility requirements in your Definition of Done. If a feature isn't accessible, it's not ready for production—just like you wouldn't ship a product that doesn't work on mobile devices or has poor performance.

This approach transforms accessibility from a burden into a standard of craftsmanship. When you decide from the beginning that accessibility is a core quality metric, you unlock innovative solutions. These efforts result in over 50 accessibility features in Diablo IV. Full button remapping is available whether you play on keyboard and mouse, or a controller. For controllers it is also possible to swap the left and right stick to aid in controlling the most important actions with one hand.

Examples of Excellence

Companies that embrace accessible design don't just meet compliance requirements—they create better products for everyone:

Lyft built accessibility into their color system, making good contrast the default choice

Blizzard Entertainment designed Diablo IV with screen reader support, controls and inputs customization, captions and subtitles, sound cues for loot, highlights for players, enemies, NPCs and more, proving that accessibility can enhance rather than limit creative expression

Microsoft has made Microsoft Inclusive Design is a practice that anyone who creates and manages products and services can use to build more inclusive experiences for everyone, showing how accessibility principles can scale across an entire organization

Apple continues to pioneer accessibility features that eventually become industry standards, from VoiceOver screen reading to dozens of other features you can check out in the accessibility section in your Apple device settings menu

The Secret Ingredient: Real User Involvement

Just as you can't create a great mobile experience without involving people who actually use mobile devices, you can't create truly accessible products without involving people with disabilities in your process.

This involvement can take many forms:

Usability testing sessions with disabled users

Regular feedback through surveys and interviews

Most importantly, hiring people with disabilities as part of your team

People with disabilities bring perspectives that can't be replicated through guidelines or checklists. They understand not just what works, but why it works and how it fits into their broader digital experience.

A Multi-Disciplinary Effort

One crucial aspect of accessible design that often gets overlooked: accessibility is inherently multi-disciplinary. It's not just the responsibility of developers or designers—it requires every team member to understand how their role contributes to the overall accessibility of the product.

Product managers need to allocate time for accessibility research and testing in their roadmaps. UX/UI designers must consider accessibility constraints and opportunities during the design phase. Developers need to implement semantic HTML and keyboard interactions. Quality assurance teams should include accessibility testing in their processes. Content creators need to write clear, descriptive alt text and captions.

When each discipline understands their accessibility responsibilities, the entire product development process becomes more intentional and effective. This isn't about adding extra work—it's about everyone doing their existing work with accessibility in mind.

The Future is Accessible

The digital products that will define the next decade won't just happen to be accessible—they'll be designed accessibly from the ground up. As more organizations recognize that accessibility drives innovation rather than constraining it, we'll see remarkable advances in how people interact with technology.

The question isn't whether you can afford to prioritize accessibility—it's whether you can afford not to. In a world where digital experiences are increasingly central to how we work, learn, shop, and connect, accessible design isn't just about doing the right thing. It's about doing things right.

Ready to Get Started?

Want to put these principles into practice? I've created a comprehensive 10 Tips Accessibility Cheat Sheet that distills these concepts into actionable steps you can print and keep on your desk, or share with your team and organization. It's designed to be a quick reference guide that helps everyone—from product managers to developers—understand their role in creating accessible products.

Comments